An Introduction to Right-Wing Radio Jock Mitch Michaels

THIS IS AN EXCERPT FROM NO IVORY TOWER, BOOK THREE OF THE MISS OLIVER’S SCHOOL FOR GIRLS SAGA

It was three o’clock in the morning and Mitch Michaels was wide awake.

Ordinarily the two Vicodins he had swallowed at midnight would have taken him all the way to six o’clock, and then there would be the limo ride to the studio where, as soon as he leaned forward into the mike, he’d imagine all those people nodding their heads, guys mostly, driving to work all over the country, their shoulders relaxing because they were hearing what they already believed, and his pain would melt away. But there was no show today because it was a holiday weekend and he was not in his New York apartment; he was in his summer house on the beach in Madison, Connecticut, and without the daily morning rage vent to look forward to and with the disturbing presence just down the hall of Claire Nelson, his daughter’s long-legged, willowy guest with the raven hair and deep-set, innocent eyes, he knew that, in another half an hour, if he didn’t take another pill, the electricity that was then a mounting tingle at both sides of his lower back would pulse down through his buttocks and explode in his hamstrings and toes like bombs going off every minute and a half. Ninety seconds exactly. He’d counted them. It never varied. The worst part was waiting in between.

He didn’t need to turn the light on to find his way down the hall to the bathroom past the room where his daughter Amy and Claire were sleeping because it was just a little shingled cottage, which he and his wife had bought when he was still a sportscaster for seventy-five thousand dollars. Seventy-five thousand! It was worth six hundred thousand now. He knew because he’d had to pay her half that to buy his half from her when they divorced—which he was happy to do—until he figured out that it made her rich enough to enroll their daughter in that school. “How would you feel,” he’d asked on his show, pretending he was talking about some other family, “if you had no say in what kind of a school your daughter goes to?”—forgetting that most of his listeners sent their kids to public schools and didn’t have any say either. The more he’d learned about Miss Oliver’s School for Girls in Amy’s freshman year—how the students addressed their teachers by their first names—or even nick names! How the kids were allowed to dress like savages and read books like Catch 22—as if they knew enough by then to know why we fought that war and what guys died for—the more cheated he felt. It didn’t help that his ex-wife, as sole custodian of his daughter, in total control of when and if he could visit with her, had obtained a court order prohibiting him from stepping foot on the campus.

In the bathroom, he opened the medicine cabinet and reached behind the row of bottles containing aspirin and ibuprofen and vitamin C and Barbasol Shaving Cream to where the one containing the Vicodin pretended to hide, opened it, and shucked two into his palm. Only ten left. He put one back and swallowed the other. He’d learned to take them without water because water was not always handy, and besides, if he drank water now, he’d have to get up and pee when what he needed was to be obliterated in sleep. The doctor in Madison didn’t know there was a doctor in New York who filled out prescriptions too—or, anyway, pretended he didn’t.

On the shelf beside the sink sat his daughter’s guest’s toilet kit. Toilet. What a nasty name for what’s in there: toothbrush, toothpaste—lipstick maybe? What else? He reached, touched the soft leather, ran his fingers where the zipper was slightly opened, then, shamed, pulled his hand away. Never before in his life had he imagined that a teenager would stir him. Girls that age, especially if they were as beautiful as this one, were people you needed to protect! He didn’t understand that this one’s ability to stir feelings very near to lust in him was a purposeful application of power, in this case just for the hell of it, and he was as addicted to being around power as he was to painkillers—because maybe they were the same. But he did understand that when the Vicodin kicked in and he was back in bed in the dark, not counting the seconds until the next explosion, he might dream of her, and because he hoped he wouldn’t and still wanted to, he was shamed still more.

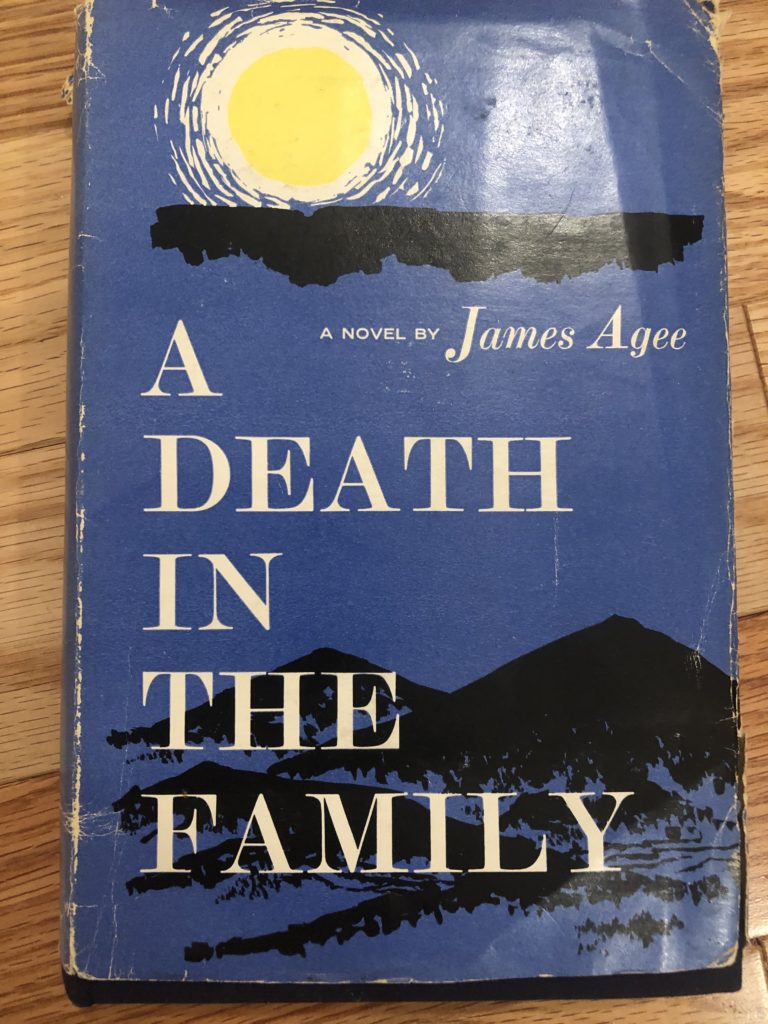

A DEATH IN THE FAMILY, BY JAMES AGEE, PUBLISHED IN 1938

A DEATH IN THE FAMILY, BY JAMES AGEE, PUBLISHED IN 1938