I went to a very prestigious, excellent boys-only boarding school deep in the woods of New England, graduating in 1949. The school was covered in ivy, both the real kind and the metaphorical. We wore blue blazers, grey flannel pants and ties to classes and to every meal, even to breakfast which was required and was served so early that in the winter it was still dark. The crest on the breast pocket of the blue blazer said Certa Viriliter. Translation: Strive manfully. Everybody knew – because everybody took four years of Latin, of course. But I liked to tell innocent visitors it meant Drive carefully.

Now that the school is co-ed, I don’t know what the crest says – or would if the students still wore blue blazers. Work hard, everybody doesn’t have the same panache. The faculty was superb; learned, passionate about their subjects, caring. Even then, I understood that some of my schoolmates were cared for more faithfully in loco parentis by these tireless people who taught four classes every day, then found the energy to coach sports, direct plays, advise literary magazines and newspapers and parent dorms, than they were by the real parents at home. Those teachers’ lives were clearly not their own. Most of them were men. I’m still grateful for the rigorous curriculum they delivered to us. Some of them had very attractive wives, the subject in that monkish boyhood world of much lurid speculation and sexual fantasy.

Most of us were WASPS whose families had been in America for many generations. Our fathers all worked in offices and wore suits with vests; our mothers all stayed home in nylon stockings, civilizing the family, running the house, doing charity work. We had one Italian, zero African-Americans, and several Jewish kids, one of whom was named Jerry. He pretended not to mind being referred to as Jerry Daju, any more than I minded Steve the Tree because I am tall.

During the summer vacation before my senior year, I dated a girl from the wrong side of the tracks. In our house my father, seventh generation Yale, Skull and Bones, required us to come to dinner in a shirt and tie – just like at school. When I picked my girl up for our dates, her dad would be eating supper in his undershirt. But in the navigation of that summer world, away from boarding school, my girlfriend was the sophisticate, not me.

In my senior year I invited her to the autumn prom weekend, the two highlights of which were the football game on Saturday afternoon, against our traditional rival, and the formal dance on Saturday night. I’m sure now, though I was too naïve to notice then, that of all the girls who came to that weekend, my date was the only one who attended a public high school. She was the only one who had to travel any cultural distance to be comfortable in a school which was also the students’ home, and where there was only one gender, where the teachers were called masters, almost everybody was wealthy and dressed all day every day as if they were going to a wedding or a funeral. I’m sure she was the only girl in attendance that weekend so may years ago who had never set foot in a country club or a yacht club and who didn’t have a parent who’d graduated from college. She went to mass every Sunday morning with her family; we went to an Episcopal chapel every evening, where the lectern was supported by a white marble statue of a knight in armor, kneeling with his sword in one hand and his helmet in another.

I was a football player, so I handed her off for the duration of the game to a friend. I like to imagine that she and he enjoyed each other’s company as they watched the game in the pouring rain. She felt shy and unsure of herself in this strange world; and he felt shy because, not being an athlete, merely a good musician and fair poet, he was of low rank. I am sure, though, that my date, who generally watched football played before large crowds on Friday nights in a stadium, wondered how such mediocre football as we played on a field next to an apple orchard could generate so much passion. She didn’t know the spectacle she was witnessing had as much to do with sibling rivalry as sport: two branches of the same royal family fighting for honor.

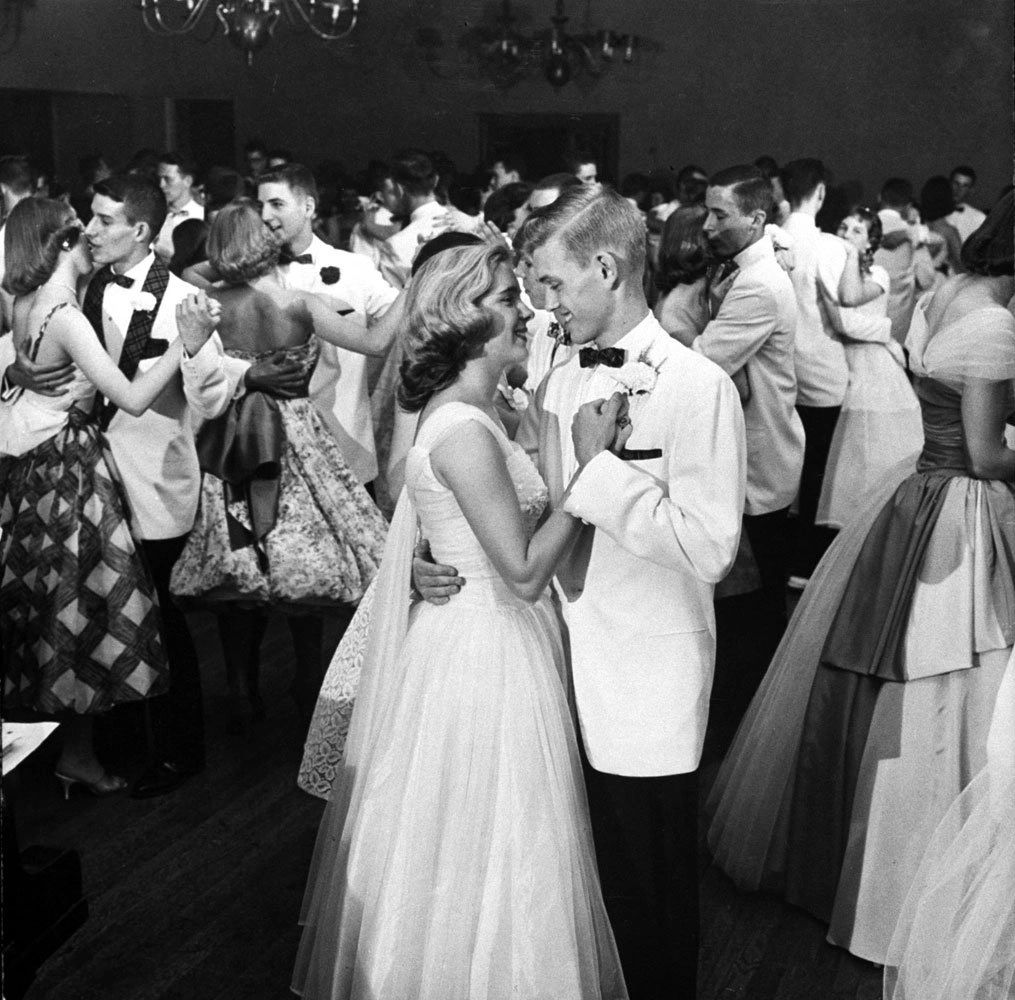

At the dance, though, my girl was a star. Not only was she a beautiful young person, she was clearly the best dancer on the floor. My friends, especially the stags, danced with her a lot. They would saunter out from the outskirts of the gym, trying their best to look like Cary Grant, and tap me on my shoulder, “May I cut in?” they’d say. I was very proud of myself –as if her beauty and her grace were my creation, but near the end when there were only so many dances remaining, I shook my head and said, “No you can’t. This was so long ago that boys held girls close when they danced. If you were in love – or thought you were – which is just as much fun and a lot more convenient- dancing was an exquisitely romantic and sensual experience.

After the dance, she and I took a walk. The rain had stopped and it was warm, but it was too wet to sit down. So, clever me, I led her to the auditorium, where as I predicted no other couple would think to go. Alone together in there, still glowing from the words of love songs we had danced to, we did a lot of hugging and kissing. Our world was a chaste one. Hugging and kissing was all we dared – and was enough. Then I took her to where she was staying, which happened to be the Headmaster’s House. It didn’t occur to me to wonder how she felt staying in a house so large it could have contained several of the one she lived in. Nor how the word headmaster would ring in her ear. I was supposed to have her there by 1am. I was vaguely aware it was past that time when we walked in.

The headmaster had steely blue eyes and grey hair, parted exactly down the center. Think a sober F Scott Fitzgerald grown tall and stern. But I’d been around long enough to look right through that stern look and see his kindness underneath. But my date had not. So, when, just as I gave her a final kiss at the foot of the stairs, the headmaster appeared in an elegant bathrobe at the top of the stairs, she must have been appalled. And when he said, half way down, still towering over us, and pointing to his wrist watch, “Davenport, you are 43 minutes late. Where have you been?” I’m sure she was. She had no idea we were late. She would not have permitted it.

“OH, are we late? I’m sorry. I must have lost track of the time,” I said, with the insouciance only the privileged can muster. I had nothing to worry about. He was too kind and too well bred to name, right there in front of my date, whatever penalty was ascribed in some ancient ledger somewhere to this particular dereliction. That would happen later, man to boy – if he didn’t forget. He wouldn’t kick me off the football team, or add a damning note to my college applications. I would have to wait table for an extra week, or rake some leaves. The rule I’d broken was the kind you felt proud of getting away with if you did, or chagrined for being dumb enough to get caught. I hadn’t cheated on an exam or stolen something from a dorm mate. “Get to bed, young lady,” the headmaster said, sounding fierce. I’m sure it was his way of expressing his relief that she was home, safe in his house. He had a daughter of his own. She moved past him and fled upstairs. I never saw her again.

She left the next morning, on the first train out, long before the weekend was scheduled to end. When I telephoned her, her sister answered the phone and told me not to call again. Home on Christmas Vacation, I went to her house and knocked on the door. Her sister came to the door and told me to please, just go away. “Tell me why,” I said, hoping that she would say that her sister left because she was disgusted with me for getting her in late, but I knew she wouldn’t. My date had been humiliated, made to feel small, less worthy than her hosts. There was no way she felt she would ever be included, even if she wanted to be.

Needless to say, the school, co-educational now, is vastly more diverse than when I attended it. We do make progress after all. It is probably unnecessary to point out, but worth pointing out anyway, that the more diverse the school is, the more energy needs to be focused on including everybody in the community so that no one will ever feel the way the lovely young woman who was my girlfriend for a very short time felt on that weekend long ago

Leave A Comment