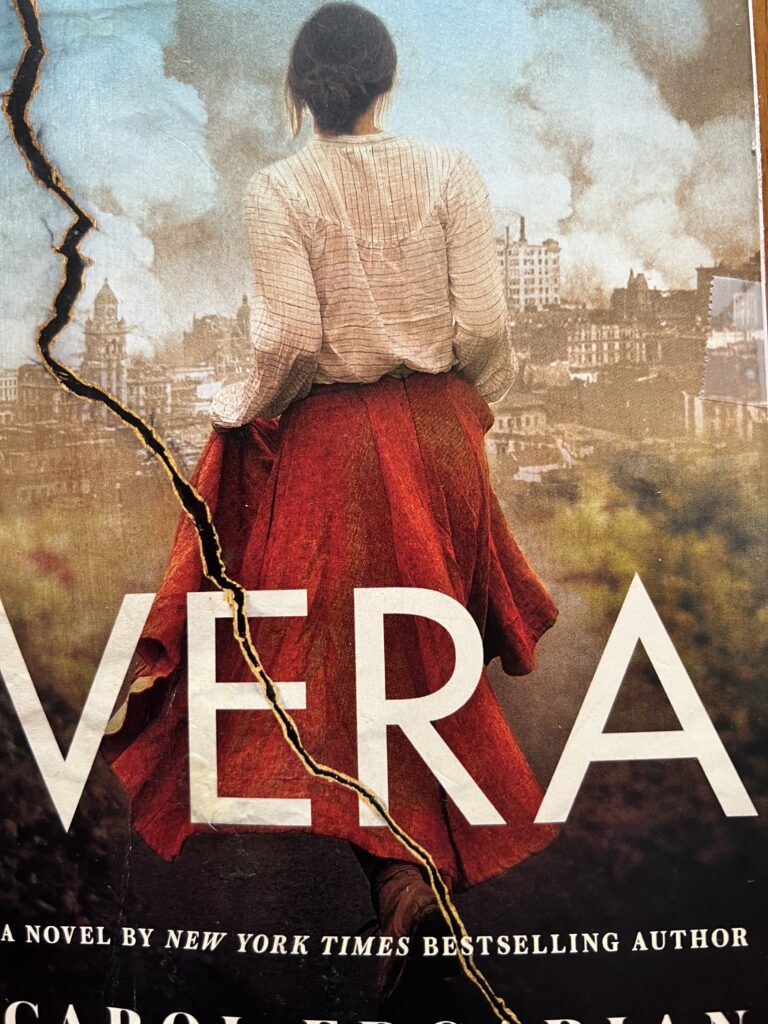

VERA, A NOVEL BY Carol Edgarian

[

Forget the history books. If you really want to know what it was like to live – or die- in San Francisco when the 1906 earthquake hit, put yourself in the hands of master storyteller Carol Edgarian, get a copy of her novel Vera, published in 2021, and start reading.

Right away you will meet the fifteen-year-old Vera who tells the story. She is the illegitimate daughter of Rose, San Francisco’s predominate madame, owner and operator of the city’s predominate brothel, named – you guessed it- The Rose. Rose, and therefore Vera also, is probably a mix of Persian, Northern African, and Spanish blood, with a suspected dash of Armenian, who, for a fee was brought north from the slums of Mexico City by the 19th century version of a coyote to become eventually the “Grande Dame of the Barbary Coast, the Rose of The Rose.” But Vera does not live with Rose, either in the brothel or Rose’s magnificent mansion on Pacific Heights – to this day unusual territory for people of such bloodlines. Instead, Rose pays a very proper, quite boring widow named Morrie to bring Vera up “to be anything but a hooker.” The foundation on which Edgarian rests Vera’s story is the schizophrenic nature of Vera’s life as she shuttles back and forth between her proper, conventional, relatively colorless environment as Morrie’s adopted daughter and the mysterious technicolor of Rose’s environment where she is befriended and even mothered by the ladies of the night. Vera’s double life is made more emphatic by Vera’s adopted sister Pie who is as different from her as Rose is from Morrie. We meet Pie, (sweety pie) at age eighteen, three years older than Vera. It is just nine days before the earthquake that will level the city when the two girls walk the family dog on a familiar loop from Morrie’s house on Franklin Street to Fort Mason and back. “Pie walked slowly, having just one speed, her hat and parasol canted at a fetching angle. She was eighteen and this was her moment. All of Morrie’s friends said so. “Your daughter Pie has grace in her bones,” they said. And it was true: Pie carried that silk net high above her head, a queen holding aloft her fluttery crown. Now grace was a word Morrie’s friends never hung on me. I walked fast, talked fast, I scowled. I carried the stick of my parasol on my shoulder, with all the delicacy of a miner carrying a shovel. ------- and anyone fool enough to come up behind me risked getting his eye poked. We were sisters by arrangement, not blood, and though Pie was superior in most ways, I was the boss and that’s how we’d go.” And that’s how it does go: it is the feisty Vera who takes the reins, makes the decisions, takes the action necessary for survival when the buildings tumble and the city burns and Pie moons over a lover who jilts her. It would be a spoiler to tell what those actions are and how it all turned out; suffice it to say here that if you want story, this novel is for you, populated with every kind of character, prostitutes, business people, kind motherly neighbors, a corrupt mayor in dire need of an emergency to prolong his career, a multiplicity of races from very level of society, one dog and two horses. And for icing on this spicy cake, Edgarian, like Dostoevsky in Crime and Punishment, identifies the specific place, naming the address of where the events take place so that if like me, you live in the Bay Area or have visited San Francisco, you feel like you are right there with Vera all the way. For me, Vera is like a Dickens novel without the boring redundancy and fluffy sentiments. A wonderful read. Bravo!

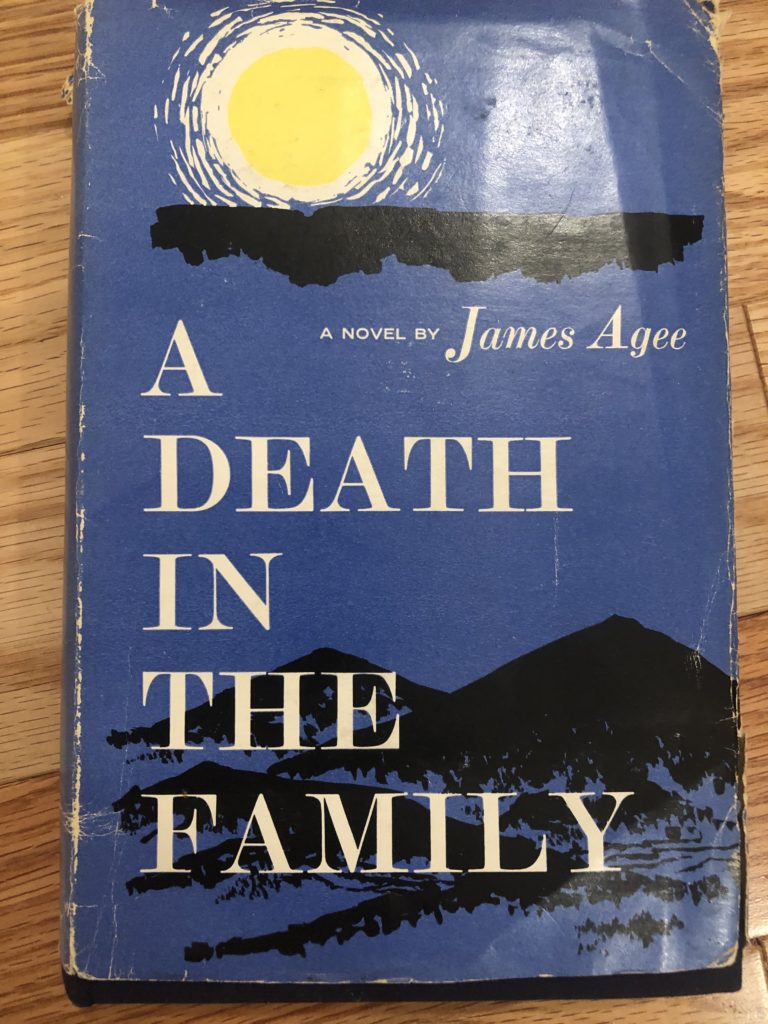

A DEATH IN THE FAMILY, BY JAMES AGEE, PUBLISHED IN 1938

A DEATH IN THE FAMILY, BY JAMES AGEE, PUBLISHED IN 1938